A Conversation With Erin Sharkey

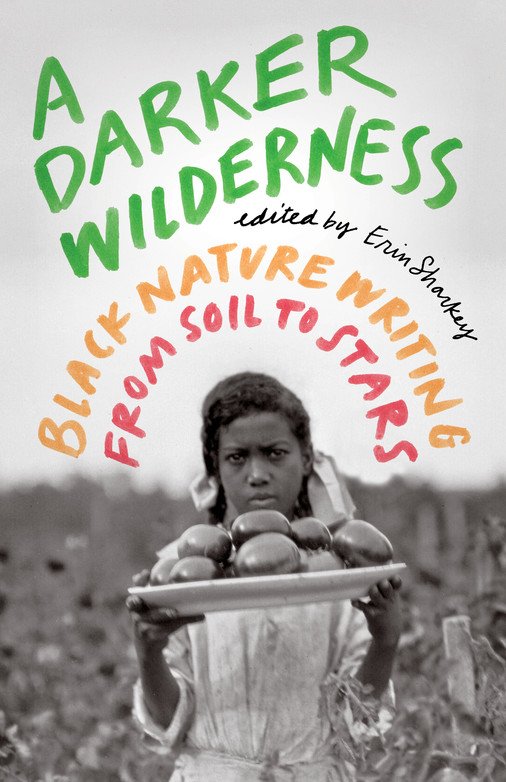

A Darker Wilderness cover from Milweed Editions

by Sagirah Shahid

“What are the Politics of Nature?”

Milkweed’s newest anthology A Darker Wilderness: Black Nature Writing From Soil to Stars navigates readers through that question. Using archival objects of Black history and memory, these essays offer a fresh and intimate mosaic of nature’s relationship with Black folks living in the Americas.

The honeyed-voiced editor behind the collection, Erin Sharkey, is a Minnesota based Black Queer culture worker who has quietly tended to the material needs of Black folks living in the region. For more than a decade, Erin Sharkey has created and organized affirming and healing spaces to disrupt violent systems and even violenter cycles.

An award-winning writer and a loving auntie, Erin sat with me via video chat to talk about her life and her recent work editing the anthology.

(Reader note: This conversation was edited for clarity and brevity)

Sagirah Shahid: Can you map out some of the intentions you had for yourself as a youth and if the visions you held for yourself have changed? Is the person you were in youth informed by the person that you have grown into at this moment?

Erin Sharkey: So I had the “I’m going to be a lawyer” dream as a young person. As I learned more about the justice/injustice system, I felt less excited about that idea. But I feel like I’m still intersecting with folks who are navigating the injustice system through my work as a teacher with Minnesota Prison Writer Workshop.

Early on in college I thought I would be a painter and I got to study for a term in the Dominican Republic—there’s a Parsons School of Design in D.R.—so I was there with some other students learning landscape painting. I got to paint flowers and the ocean every day. I started writing inside of the paintings, like on the paintings, and I had a professor say “maybe you want to write stories?” And I was like “oh, maybe I do?”

I went on a meandering journey as a political organizer. I worked for Paul Wellstone’s staff here in Minnesota before he passed and that sent me on a weird journey to New York. After his death I made a really rash decision that I would move to a city I only visited once (Buffalo, New York). I thought I’d be there for 9 months as an AmeriCorps volunteer but I ended up being there 10 years. I fell in love in lots of ways with a city, with a neighborhood, with a person.

I think I’ve learned more about myself and what I’m good at. I’m good at people stuff. I’m not an extravert necessarily but I definitely like people. I think I must be descended from a bunch of engineers because I can see how a thing works, like how a system works and that helps me as a producer, helps me as a teacher, helps me in lots of ways.

Erin will be joined by writers Michael Kleber-Diggs, katie robinson, and Tia-Simone Gardner Thu, Feb 2, 7pm at Open Book: A Darker Wilderness Book Launch Event

I try to bring my best to projects. Right now I’m really focused on art and rest as key components to social justice and the world. In Minnesota, “Up North” culture is a thing, but the reality and benefits of being in nature and being in rest and being away, has been experienced by some people in Minnesota.

So it feels exciting to be able to offer that access to rest to folks who are on the frontlines doing organizing work, folks that are making art, folks that are confronting hard questions, people that are… Tired.

A Darker Wilderness feels like a timely convergence of work you’ve been doing. What does the arrival of this anthology feel like? How did you arrive to the contributors you’ve included in the anthology and what lessons have you learned throughout this project?

I had been trying to think about how to reflect on my time as an urban farmer. I thought this is an interesting thing to think about in terms of structure… There are rhythms in urban places. You don’t have to go to the country to find there are rhythms or natural patterns of things—we’re a part of nature.

In the city there are natural rhythms of things too. When people start grilling, or like when you hear that particular sound of the basketball on the court, the chains moving on the basketball hoop, when someone starts to change the oil of their car. It was such a gift to me to have a container for these essays. They actually started as poems (most of my essays do).

I wanted to gift the contributors of A Darker Wilderness that process. I had a dream list of people that I wanted to ask to be a part of it. I just loved them as writers. I wanted to see what they would do.

As a way of introducing the project, I shared my essay with the contributors and I shared 5 or 6 objects that I felt might intersect with their interests, or the regions they lived in, or something about them that I knew about. Some folks latched right on to those objects. Other folks wanted all the objects. Other folks, we went on a journey together in the archive, to try to find things that they could have conversation with. That was my favorite part of editing.

photo by Soraya Zaman

One interesting part of the writing process was that I asked them to write a pretty long essay. Often, in anthologies essays are seven pages long. These are more. I really wanted the contributors to get into it.

I asked them to be part of this book right before the pandemic, right before the Uprising. In 2020, Black writers were solicited for work like crazy, I myself was solicited for work in a wild way. So it was stressful, for all of us to be in the pandemic, for us to live with an awareness of such violence, violence right close to many of us.

2020 shifted things for our region and our bodies. I’m curious to know what your physical body, with all of its wisdom(s), requires of you now that the landscape of Minnesota has been jolted?

I think the big thing I did in 2020 was step into stewardship of Rootsprings.

Having a relationship with land, and a land that’s specifically centering Queer folks and People of Color and keeping that in mind while organizing with Black folks and Black artists in particular, that’s felt like it's been life giving for me and health giving too. To be able to create a place to receive people.

We do a lot of passive programming there. Which just means we say “yes.” We’re like, you can do these things. Would you like to snowshoe? Or like, you can walk the labyrinth or we have a library, it's not a lot of active programming. We’re really wanting the land to receive people and to let folks choose their own adventure.

And yeah it feels like my body is responding positively to that.

“The Fields at Rootsprings is stewarding liberating space for BIPOC artists, activists, healers, and community centering LGBTQ folx.”

Black and Indigenous folks in this country have very specific histories and oppressions we navigate regarding land and its stewardship that intersects. I would love to learn your thoughts on how our communities might navigate our relationship with each other, in a way that affirms our connections without negating the unique complexities of each community’s oppressions. In your opinion, how do Black folks and Indigenous folks authentically show up for each other?

I want to continue to consider and wrestle with this question. Both of our communities are owed reparations. It's important for us to not allow them [our oppressors] to pit us against each other. I want to learn more about Minnesota and the Indigenous People in Minnesota.

I was just watching a TikTok with a creator who was talking about how much of the reservation land in Minnesota is not owned by Native People, it's owned by individual folks. They showed a map and I was like holy cow, there’s so much space that’s owned by white people inside of reservations. I want to be more mindful of that.

We acknowledge that our land, Rootsprings, has a long relationship with Native folks and there’s a group of Indigenous women who have used the land for sweat lodges. And that feels like a really important component that we want to continue to center as we go forward with this work, to make sure that the land is still shared so folks can do their sacred sweats and other practices–to share resources as we invest in the land, so they have resources for their work there.

One of the essays in the collection was written by Lauret Savoy. The essay talks about name-place changes, changes to place names that are racist and tracking them. Relooking at this article she wrote 15 years ago now, I’m thinking about what are the questions we need to ask now.

In Minnesota we have way more questions to answer. To think about how we atone for our history, to think about how our history is tied to one another and fighting every time they [our oppressors] try to tell us we can’t all have justice, we can’t all have access—thinking of the third way or the fourth way—thinking of how we don’t need to settle. I think it's being in a position to learn.

I think our relationship to place is an exciting opportunity to connect with one another. To think about all the journeys that brought us to this place, our short or long relationship with it. There’s a lot more to learn. And I think that’s connected to this idea of the archive.

Our relationship to history doesn’t have to stay in the past. Time moves in a way that allows us to reflect, to rectify, to tell a more honest account of things.

We’re not isolated from it. It matters. It matters what we call things. It matters because it can reaffirm ideas of power-weirdness or like, reinvest in these ideas of “manifest destiny” that are not going to save us.

We really need to think about how we can learn the lessons we need to learn, to right things that have been wronged.

A Darker Wilderness book launch

Black nature writing from soil to stars

In partnership with Milkweed Editions

With Erin Sharkey, Michael Kleber-Diggs, katie robinson, and Tia-Simone Gardner

Thu, Feb 2, 7 pm

Open Book Performance Hall

Erin Sharkey is a writer, arts and abolition organizer, cultural worker, and film producer based in Minneapolis. She is the cofounder, with Junauda Petrus, of an experimental arts collective called Free Black Dirt and is the producer of film projects including Sweetness of Wild, an episodic web film project, and Small Business Revolution (Hulu), which explored challenges and opportunities for Black-owned businesses in the Twin Cities in the summer of 2021. Sharkey has received fellowships and residencies from the Loft Mentor Series, VONA/Voices, the Givens Foundation, Coffee House Press, the Bell Museum of Natural History, and the Jerome Foundation. In 2021, Sharkey was awarded the Black Seed Fellowship from Black Visions and the Headwaters Foundation. She has an MFA in creative writing from Hamline University and teaches with the Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop.

Sagirah Shahid is a Black Muslim poet, arts educator, and performer. Her poetry and prose are published in Mizna, Winter Tangerine, Juked, and elsewhere. Sagirah is a poetry editor at Overtly Lit.